Audio version Kratom Science Podcast #42

KratomScience: Canada was one of the first countries to fully legalize cannabis. This was in 2018. Has there been an impact on the research that you can do in Canada because of legalization?

Dr. Zach Walsh: Yes and no. The big moment for us with legalization and research really was when, through a series of court victories, they revised the medical cannabis program to allow for licensed producers. It used to be that you could only get your cannabis from a single producer that was hired by the government. They had a limited range of cannabis products that were not widely accepted by medical cannabis patients. That’s why the dispensaries cropped up. Yes, there was a program, and yes, it was legal. But the government product was not satisfactory to most patients. So they were allowed to grow their own. But it was revised to say, okay, we’re going to have a competitive model where there’s going to be for-profit companies that are producing cannabis. When that came on board, all of a sudden there was product that we could use that was for research purposes, so we could do research with good quality cannabis, and there was an industry that was supportive of that research. And that was a couple years before broad legalization. I think it was three years before we legalized entirely, that that amendment was made, and that’s really what opened up the research for us. All of a sudden there were companies that could be partnered with that could provide cannabis. That was in a way a bigger change than legalization itself. If anything, legalization in some ways makes medical research more difficult. Just because, if you’re trying to do trials, everyone has access to cannabis anyhow. Paradoxically, people are not particularly interested in being part of all the rigamarole of a clinical trial when you can just get the medicine quite easily at a corner store.

Here in the United States we have cannabis that’s allowed to be used in clinical trials. It’ grown by the NIDA in Mississippi. You had mentioned in one of your talks that it’s “grown with disdain”, which is pretty funny. Because it’s so low quality and it includes stems and seeds, and it sounds like the stuff I used to get in high school.

I can’t speak to the mental state of the growers, and I’m sure they’re very talented. But they’re limited in what they’re allowed to produce. I know I’ve said that and I wince a bit about it. It appears as if it was grown with disdain. One can be forgiven for assuming that based on the end product. But I certainly don’t want to infer that the people who are working hard in the Mississippi farm where I believe it’s produced still have disdain for it. I think that they’re probably quite into their work and doing as good a job as they’re able to do given the restrictions.

But it’s not just me, there’s a study from the team of Cinnamon Bidwell from University of Colorado and other places that looked at that NIDA cannabis and compared it to what’s in dispensaries. Even from a chemical analysis, it has a different cannabinoid profile largely because it’s so old. It’s not like what people are using medically. It hurts the validity of the research. That was our position in Canada for a long time too, until the licensed producer laws. Now we can get decent weed for research.

In your TedX talk, you talked about the history of cannabis going back millennia. What do we know about why people first started to use cannabis?

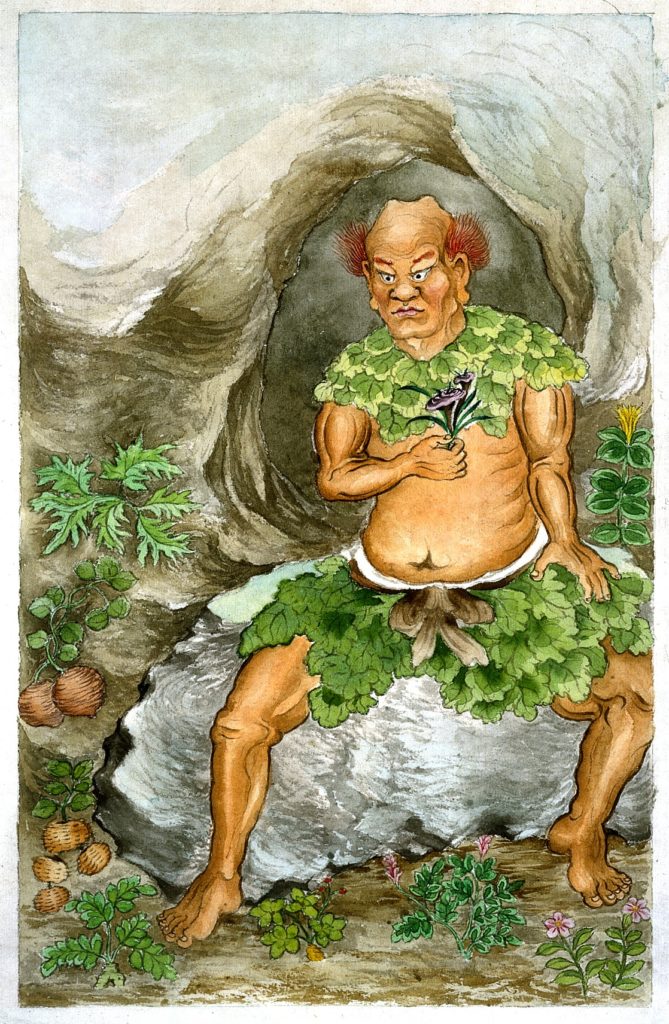

The short and cheeky answer to that is ’cause it works! It has a profound undeniable effect which also feeds into some of the difficulties of research. Everybody wants placebo controlled research, but when everyone’s tried cannabis, people tend to know if they’re in the placebo condition. It’s always a wonder how humans first assayed these different products, whether it’s kratom or cannabis. But we know that the history of it is from central Asia, from China. It goes back to that time in our history when medicine and religion and science were less separate. Shen-Nung is the historical figure in the Chinese literature who is also attributed to discovering tea. If you look at pictures of him, he doesn’t look entirely human. So it’s sort of a shamanic healer/historical figure who is thought to have introduced cannabis. To the extent that he was an actual figure or a composite of a bunch of different folks, or just a conduit of healing traditions, there’s probably some anthropologists or historians who would have better things to say about that than me. The take home is that it goes back to prehistory. It’s a long history, a synergistic history. It’s sometimes called the “trail follower”. We know that cannabis pops up sometimes where humans have disturbed the ground. Sometimes I like to make the analogy, it’s like a dog. There are so many different varieties. I think kratom is like that in a way as well. I don’t know if kratom has been as comprehensively documented, at least in the English literature. There’s probably some really great stuff out there for someone who can dig it up. But a lot of plants have emerged in partnership with humans. Humans help them to spread, and they help humans. So it’s sort of a synergistic relationship.

Along with that, we’ve recently had some fear of cannabis and prohibition. We can trace it in recent American history back to the 30s with Harry Anslinger. Is there any evidence of a reaction like this to cannabis or any substances prior to, say, the 19th century?

Substances that are psychoactive, that change our consciousness have always been so highly prized by different societies that I think they become emblematic of the societies that use them. Certainly you can see how alcohol has been integrated into Judaeo-Christian traditions despite the public health consequences of alcohol use that’s really enshrined. You wouldn’t want to try to get rid of it. It’s just part of the culture. It’s the same with other substances. When cultures clash, they often demonize each other’s substance. There was a time when you could be put to death in Germany for coffee because it was thought to be an infidel’s beverage. When I look at the long history of drug prohibition, it’s not just us that have had these crazy ideas about trying to villainize substances and the people who use them. And we pick some for seemingly random reasons, despite how dangerous they actually are or aren’t. And we pick some and say they’re great and others and say they’re evil and people who use them should be punished, etc. It’s not a unique thing, although like many other terrible things, it’s been perfected in the modern era.

With kratom that’s kind of what people are dealing with. It seems to work for most people and be relatively safe. The study you did with Dr. Marc Swogger and the folks that run Erowid.org shows that most people, in self-reporting anyway, show that it’s been positive, with few side effects. And then we see case studies that are single cases of people developing an addiction to kratom, or maybe mixed it with something else and got sick. One guy got shot and they called it a “kratom-related death”. Some of theses are clearly trying to accentuate the negatives. What accounts for that?

Well, it’s almost a case study in drug hysteria isn’t it? That’s one of the things that really interested me about kratom right off the bat. It’s kind of obscure to most people. So it’s almost like an inkblot test or something. How different agencies and organizations respond to kratom says a lot about how they respond to drugs more broadly. There’s certainly a group of people where there’s this almost knee-jerk enthusiasm for finding a problem with kratom, and exaggerating it based on some kind of a drug hysteria. My sense of it is, like anything, it’s not entirely benign. Certainly it can cause a bit of a dependence. But in terms of the acute risks of it, I mean, we tolerate so many dangerous things in our society. I live in the mountains of British Columbia and there’s people skiing all the time, and I see students come in with broken legs and you go to the hills and you see people carried away on stretchers. Yet we don’t seem to have any problem with the fact that people enjoy skiing. It does something for their health and well-being and they’re allowed to do it, and nobody would think to prohibit that. Yet I would suggest skiing is every bit as dangerous as kratom.

I definitely would not ski and I take kratom a couple days a week.

And no one’s had to carry you out on a stretcher for a kratom-related accident?

Not yet.

We don’t even quantify those risks. You can do case studies of people skiing – it’s terrible.

In a talk from 2019 entitled “Cannabis Revised“, you mentioned an article that Malcolm Gladwell wrote about somebody that smoked pot and went on a murderous rampage. His source was a psychiatrist. Does the field of psychiatry in general have an embedded vendetta against substances like kratom and cannabis?

I know a lot of really great psychiatrists. A lot of people in mental health generally are there because they want to try to alleviate suffering. I would say that’s almost everybody. But at the same time, there’s a conservationism in the medical field, and when it comes to psychiatry, they’re the gatekeepers of normal. They have a quasi-religious status in our society of saying what’s sane, what’s okay, what’s admissible. So they’re defensive of things that come from outside their purview. And that includes substances like kratom and cannabis that come from other cultures and have ancient histories that are steeped in religions and mysticism and other things that are maybe in-congruent with their training. A new drug can come down the drug development pipe, and it should be mysterious. It doesn’t have thousands of years of anecdotal use, but because the medical establishment feels comfortable with this pathway, even though there’s not much known about these drugs, they say oh yes, this is promising, this is exciting, we should try it, and if people have bad results they should stick with it until the good results show up, etc. But then something like kratom or cannabis comes along, and they’re like wait, we don’t know anything about this. There’s not enough research. It’s really a bit narrow in what constitutes evidence, and what constitutes truth. It’s an epistemological issue of how do you know when you know? If you only want to know about safety and effectiveness of substances of what can be found from a clinical trial then that is all you know, and you can say that there’s nothing known about things like kratom and cannabis. But if you want to look at what people have been using for a very long time, and what do we know about traditional uses, then there is a lot you can know, and maybe you know more than you do about these pharmaceutical drugs, really. It really comes down to, what does it mean to know? And how quick some psychiatrists and medical establishments are to say there’s not enough evidence, we don’t know anything. And really what they’re saying is, we’re keeping a gate on truth. And what’s true is what we can say. And how do you enter the club of what’s true? Well it takes a lot of money because you have to do these RCTs. That really limits what can even be tested. Something like kratom or cannabis, there’s limited ability to put them through an RCT pathway. It’s not “one size fits all”. There are several constituents, they are not single molecule medicines, and they may have limited commercial potential that would pay someone back for spending millions of dollars on a drug development pathway. We can all solemnly nod our heads and say “Yes, we need more RCTs.” But if we wanna be pragmatic and say, hey, maybe these RCTs aren’t going to happen. Where are we left? Do we just discard these medicines when they appear to have potential to treat things that are under-treated? When they appear to have potential to compete with other medicines that have really problematic side effects? These are the questions that guide my research and my science.

“A lot of plants have emerged in partnership with humans. Humans help them to spread, and they help humans. So it’s sort of a synergistic relationship.”

What are people reporting about why they use medical cannabis today?

Medically the big reasons are pain, sleep, anxiety. Those are the big three that keep coming up again and again in all the surveys. And then there are different sub-clusters of patients who use it for a variety of different reasons from gastrointestinal issues to nausea, epilepsy, muscle spasms, etc. But those are more for specific conditions. If you look at pain, anxiety, and sleep, even the people who are using it for those other conditions will often report those as side benefits. I mean, managing pain is a big thing and that’s a big piece of kratom and cannabis as well. I’m interested to see how kratom and cannabis work together. Certainly anecdotally we hear a lot of people having some good effects there. It is tricky to do the research just because kratom does remain slightly obscure. It’s hard to get good samples of kratom users. I know Oliver Grundmann and some other colleagues of mine are doing a great job with that.

Is there a difference between medicinal and recreational use. My question is, isn’t it all kind of medicinal if you’re using it to change your mental state?

I think there are blurry boundaries. There are some folks who use cannabis, let’s say, for seizures, or for nausea, etc, where it’s very effective and they may not even like the psychoactive effects. So it’s a negative side effect – I wish I didn’t feel this way but the payoff is worth it. And then there are other people who wouldn’t describe themselves as having a medical reason. They just like to get high. Those two things are not the same I don’t think. And then it’s even more complicated because those people who use it medically might sometimes use it just to get high. And some people who use it primarily because they like to stick on the headphones and listen to some tunes while they’re stoned – they may sometimes use it for a medical reason. I don’t think we can put firm boundaries between those.

The analogy of a dog is helpful. If we were to ban dogs because they’re a nuisance, they bite kids – protect the kids – that’s always a big thing in drug prohibition. Say “90 percent of dog related accidents are due to kids” I don’t know. You could make a case as to why. I would never want to ban dogs, but you could make a case that they’re a nuisance. If you were to revisit that, you might make exceptions to people who are visually impaired. You might say, “Well those people really need a dog, so let them have a dog.” Maybe there are people who are isolated and lonely with depression. That might be the next people you can open it up to. Eventually you’ll say, everyone can have a dog. How sad do you have to be to want to be cheered up by a dog?

There are some cases where people really need the medicine, and it might be purely medical. There’s other cases where it’s not medical at all. But for a lot of us it’s a mixture of being comforted by another species, a plant species, and having a relationship with that plant that is beneficial.

You talked about the term marijuana having racial overtones. A lot of people might react and say, maybe that’s just political correctness. But I think language is more important than that, isn’t it? We’re calling it cannabis now because we’re acknowledging why it was outlawed in the past.

“Political correctness” is really in the eye of the beholder. When someone accuses someone else of political correctness, they’re saying “Shut up. What you’re saying is not relevant.” If that’s what you mean, just say that. Don’t accuse me of something odd. If somebody wants to call something something, they have a reason for it. That argument when it comes to cannabis really doesn’t hold much water, because the reason they switched it to “marijuana” in the first place was because of that reason, because calling it something matters. Everyone knew about cannabis as a medicine, mostly in tinctures. It was an over-the-counter medicine. So if you’re going to make some new drug scare around something, you can’t just call it the thing that everybody already knows, like “Iburprofen Mania”. You’ve got to make something new. So they made it “marijuana” and tried to characterize it as coming from Mexico, when really it’s an Asian plant that was well known, and came from China to India to Britain to the US. But they made it marijuana from Mexico, and really did tie it to racism straight up. I don’t think there’s much debate that the War on Drugs is racist. There was a time when that was debatable. I’m glad to see that debate put to sleep. It’s racist. That’s one more reason why it’s got to be stopped. It’s always been racist. That’s why we villainize some drugs and not others. That’s why kratom, seemingly innocuous as it is in many ways, has the potential, maybe if we learn more about it, to help us with this terrible opioid overdose epidemic, that’s a real real real threat, but yet it’s being villainized because they can find one case report from Sweden where someone mixed it with something dangerous, then had a bad outcome. But part of it is because it’s this exotic drug. What is it? We’re scared of it because it’s exotic. If someone were to manufacture kratom, it would be considered a very promising pharmaceutical.

It’s crazy that they haven’t yet. It seems to be helping more people than it hurts. It’s not a clinical trial, but there’s no reason these people are lying.

I know right? There are deep questions around what makes a medicine and what makes it effective. One of the things we find in the cannabis research, is we’ll ask someone “How is cannabis helping you?” They’ll say, “It really helps my symptoms.” But if you track them over time, their symptoms don’t get any better. So one objection that people have to the kind of research that I do, is that people just think they’re getting better, but they’re not getting better. You have to wonder, is thinking you’re getting better a kind of getting better? What’s the standard for what’s helpful and what’s effective. I don’t think it’s fair to dismiss all these anecdotal reports. In the absence of pronounced risk, which seems to be the case with kratom – we don’t see terrible cases, they have to dig pretty hard to make these cases against it… If people seem to think that it’s effective, I think there should be a weight on that. I don’t know why people are so concerned about kratom when there are so many dangerous things in the world. Why kratom?

You said in a talk that when studying psychedelics, we need to consider a little bit of magic and a little bit a skepticism. Can you elaborate on that? Do scientists need to consider a more spiritual perspective? Or do spiritual people need to consider a more scientific perspective when it comes to psychedelics?

I guess what I’m saying there is just because you’ve described something in one way doesn’t mean you’ve described it entirely. We have to be open to the fact that we’re not going to capture all the effects whether it’s in a randomized clinical trial, or whether it’s in these cross-sectional designs, or whether it’s in some of the more esoteric, fanciful descriptions. All those give us a perspective on the experience to help us understand it in different ways. There are ways in which contemporary western medicine and magic and ritual are still entwined. Maybe part of what we see with this interest in plant medicines like kratom, psilocybin, and cannabis, beyond just whether or not they’re more effective than a pharmaceutical – many people say there is something more appealing with those kind of approaches than pharmaceuticals. There can be a tendency to write that off and say “Just because something is natural doesn’t mean it’s safe” and “What do you even mean by ‘natural’?” and “That’s just a flaky idea” but I think we do a disservice to genuine longings of people for a different kind of approach to health and wellness and a connection to the way things might be that’s a little different than our current medical paradigm. It hasn’t always been the way it is now, and it’s going to change in the future too. So I think we want to stay open to what these plants bring us, not just try to shove them into the existing model of pharmaceuticals and say, “Kratom is just as good as a pharmaceutical”. Maybe in some ways it’s better, and in some ways it’s worse, but I think we want to make space for that.

“I think we do a disservice to genuine longings of people for a different kind of approach to health and wellness that’s a little different than our current medical paradigm. It hasn’t always been the way it is now, and it’s going to change in the future too. So I think we want to stay open to what these plants bring us, not just try to shove them into the existing model of pharmaceuticals.”

Psychedelic psychotherapy is something that’s being explored again recently, after a big gap starting with the War on Drugs, along with demonization of psychedelics and stories about people jumping out windows after taking a hit of acid. What does a psychedelic therapy session look like?

The typical model – I don’t think there’s a standard that has solidified yet, but there’s definitely converging approaches. What I think is consistent is, a couple of non-drug sessions of preparation, and a couple of non-drug sessions for integration. So you get ready for the experience, you focus yourself, and then you unpack it afterward. In terms of what the actual session looks like, it’s sort of like a procedure in which people will mostly be quiet, sleep masks, headphones with usually a pretty well-tailored soundtrack that’s emotionally evocative but not too distracting – so not a lot of lyrics, or any lyrics usually, and the presence of a therapist. But the therapist is typically not that active, especially at high doses. It’s not a place where you want to be doing a whole lot of talk therapy other than to reassure someone to let them go back and have their experience. There’s time to talk about it in subsequent sessions. But really if you were to see someone doing psychedelic psychotherapy, if things are going well, mostly you just see someone lying on a couch with a sleep mask and maybe some headphones on, and someone else sitting by their side.

No lyrics – that kind of reminded me of the Grateful Dead. I saw you used Jerry Garcia in one of the talks. I saw the Grateful Dead twice under the influence of psychedelics, and they jam out without a lot of words, and it seems to work.

I saw the Grateful Dead more than twice under the influence of psychedelics.

I don’t know if what that was can be explained in science. But it was fun.

It was for sure fun.

You published a study called “Reductions in Alcohol Use Following Medical Cannabis Initiation”. I’ve had problem drinking in the past and I know cannabis helps me with my intention to stay sober, in that I don’t have to be in my same annoying sober brain all day. Is that kind of the mechanism by which cannabis helps with alcohol cessation?

I love that question. That’s one of the main areas of interest for me in research, is how cannabis works as a substitute. It’s the same with kratom. If we’re going to look at the real public health benefits, we have to get a little more complicated and say well, maybe the benefits aren’t direct, maybe they’re indirection through reduction and the use of other substances. With kratom, it’s obviously opioids. With cannabis, it’s opioids too but it’s also alcohol. Alcohol is the most consumed drug, and it’s the most problematic. Even with the opioid overdose epidemic, I think the public health costs are still greater. If cannabis reduces alcohol use, then that’s great. Potentially, it could increase it too. If you look at something like cocaine, it makes people drink more. Not all drugs are substitutes some are compliments. In the case of cannabis I think there are a couple mechanisms of how cannabis reduces alcohol use. One can be the kind of thing you were talking about, where it’s a direct, mindful substitute, where you say I’m not going to drink alcohol, I’m going to use cannabis instead. That maybe makes it more acceptable. It feels like less of a sacrifice if you know at the end of the day, instead of having a drink, you have a puff. It does pretty much the same thing, it gets you out of your head and creates a buffer between one part of the day and another. That’s probably a lot of it. One thing we’re interested in and this hasn’t come out yet, one of my masters students just finished up a study looking at binge drinking. That’s where the concern is with drinking, if people are drinking maybe more than four or so drinks on an occasion. Once you get past five or six drinks, that’s where you get into this danger zone where each additional drink increases risk of accident and negative outcomes. So even if you can cut someone’s binge from seven beer to six beer, even though that seems like a small thing, at a public health level it can be quite a savings. I think cannabis works there too. I think it causes people to drink a little more slowly, and maybe forget where they left their beer, or that they even opened one. That’s one of the things we found in our study, that cannabis combined with alcohol, people drank about a drink less in a binge. It might not have even been that intentional. They may not have meant to. They just ended up drinking a little more slowly because they were smoking at the same time. Anecdotally, I’ve had that happen.

There was another study you did on psychedelics and intimate partner violence. It had to do with the ability to regulate emotions. It showed that people who had used psychedelics are less likely to be violent.

It looks like that it’s associated with better emotion regulation. I think that feeds into some of our ideas about how psychedelics might work. They just give you a little bit of perspective on your emotions, so that you can experience it as an emotion instead of being entirely fused with it. So it’s just like a fact, I gotta react to this, this is real, I’m being threatened, or I’ve had enough, or whatever. You have that little bit of distance on yourself. I can just have that thought, and I don’t need to react to it, and I can just keep living my values, which for most people is nonviolence.

Yeah that’s why I’ve never seen a fight at a Grateful Dead show. Or if I did it was because they were drinking.

They were remarkably peaceful events considering the level of intoxication.

###